Remembering the Mother of London’s Notting Hill Carnival, Claudia Jones and Her Fight for Black Dignity

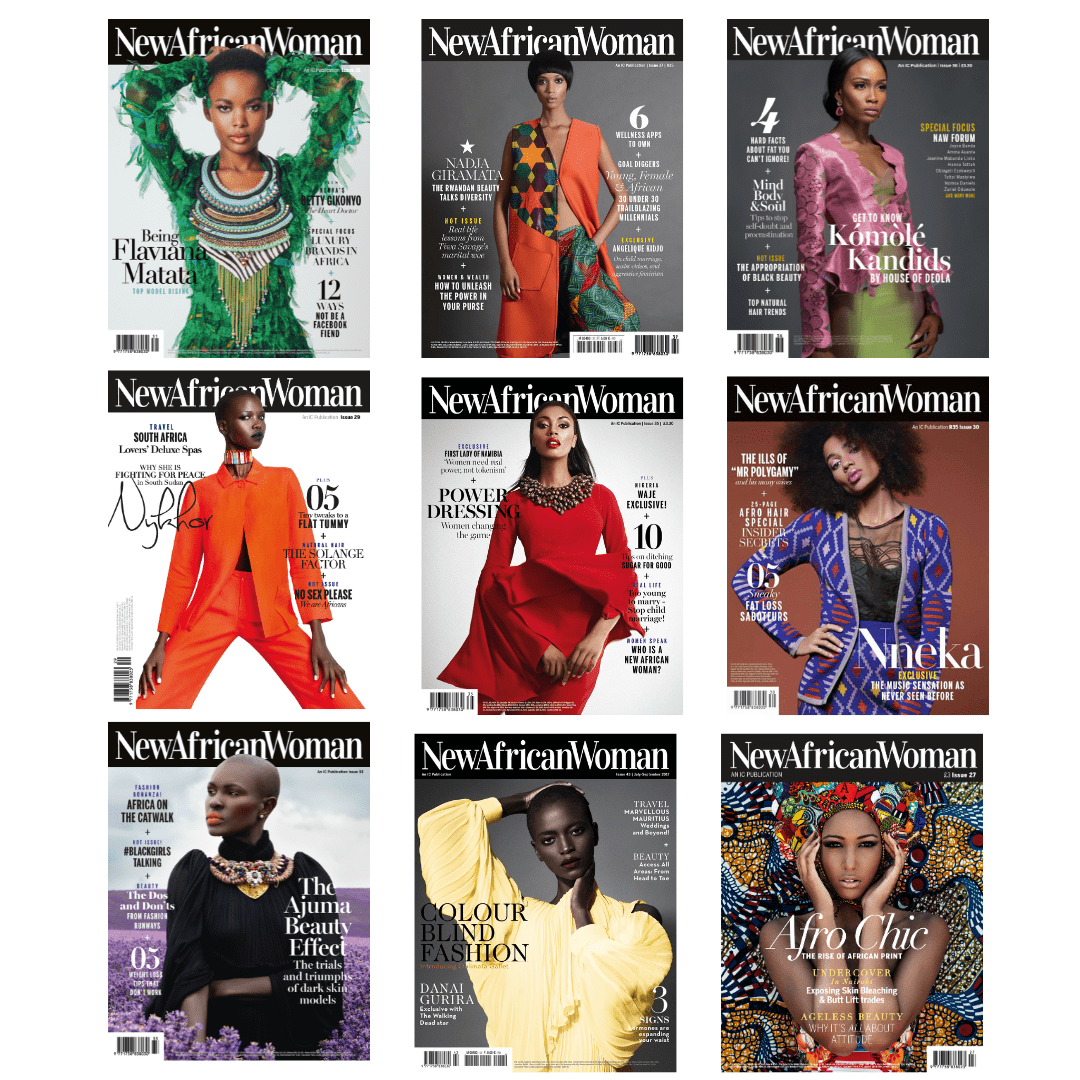

One of the heroines of Black Britain was Claudia Jones, a fighter for black dignity in the USA and UK, founder of the first black newspaper in the UK, and the mother of London’s Notting Hill Carnival. Clayton Goodwin traces the life and times of this amazing woman.

The time that the Caribbean/African community decided that they had a permanent place in Britain – and that they would not be “going home” in the foreseeable future, as so many had imagined hitherto – can be pinpointed exactly. The turning point for the fightback as a community against adverse social and economic conditions, and the increasing manifestations of hostility, can be traced back to January 1959, when Claudia Jones realised the foundation of the London Caribbean carnival.

But Claudia’s life was an apparent counterbalance of contradiction. She was born Trinidadian, considered herself to be American, and has come to be seen as the embodiment of the West Indian struggle in the UK. And struggle is the operative word for her life, especially in her final years in London, when the effects of the ill health which had dogged her for so long were exacerbated by the pressure of unpaid bills, brought on to a considerable extent by the costs of establishing the West Indian Gazette newspaper and the fight for what was seen at the time to be a minority cause.

“She was a vigorous and courageous leader, very active in the work for the unity of white and coloured peoples and for dignity and equality, especially for the negro people and for women.”

Claudia died alone and broke on Christmas Day 1964, from a heart attack and the effects of tuberculosis. She was only 49. Her body was not discovered for two days, but her funeral, and her burial next to Karl Marx in Highgate cemetery in North London, attracted many mourners.

Fragile illusion

She is acknowledged today as an icon of Africa, African-Caribbean and feminist causes. At the time of the founding of the West Indian Gazette, as1958 turned into 1959, race relations in the UK, and throughout the world generally, were at a watershed. The riots in Notting Hill had shattered the fragile illusion that all was well. The veil covering what had been a twilight world for the national media and the majority host population, and, indeed, for a good number of the then immigrants, had been pulled aside.

Aspects of the lives of the West Indian community, which many preferred not to recognise, were brought into sharper public focus. The situation required a locally-based spokesperson to coordinate and to give voice to the community’s feelings and aspirations. Yet such a person was hard to find. West Indians, as the name implies, came from not one but several territories in the Caribbean, and did not have a single structure of experience. Those with political, oratorical and administrative acumen – although they may have studied in Britain – usually returned to the Caribbean or to Africa to further the struggle for independence there. Those that made the trek to Britain (and stayed) were mainly manual workers, whose time was taken up fully in working, or in the search for work or housing (“No coloureds, no irish, no dogs”, white landlords insisted in those days).

Those manual workers were accustomed to having others take decisions on their behalf. However, they laid the foundation on which those that came after them could take advantage of the better prospects for education, employment and social advancement to be found in Britain.

Enter Claudia Jones

Claudia Vera Cumberbatch Jones came into this situation in 1955 as a ready-made fighter shaped by her experiences in the USA. She was born on 21 February 1915 and was 9 years old when she joined her family in Harlem, New York. At her junior school, she won the Theodore Roosevelt Award for Good citizenship: it is said that her family were so poor that she could not afford to buy a gown for the prize-giving ceremony.

The adverse social and housing conditions in which she lived were so unhealthy that in her teens, she caught tuberculosis which damaged her lungs, a condition she would suffer from throughout her life.

Claudia’s political commitment was framed by the case of the “Scottsboro Boys” – in which nine African-American youths were falsely accused of raping two white girls. The ensuing long-drawn-out legal action achieved a high international profile in the late 1930s, due primarily to the communist Party (of the USA) taking up their cause. Claudia joined the party, becoming national director of the Young Communist League in 1941, and seven years later was elected to the national committee.

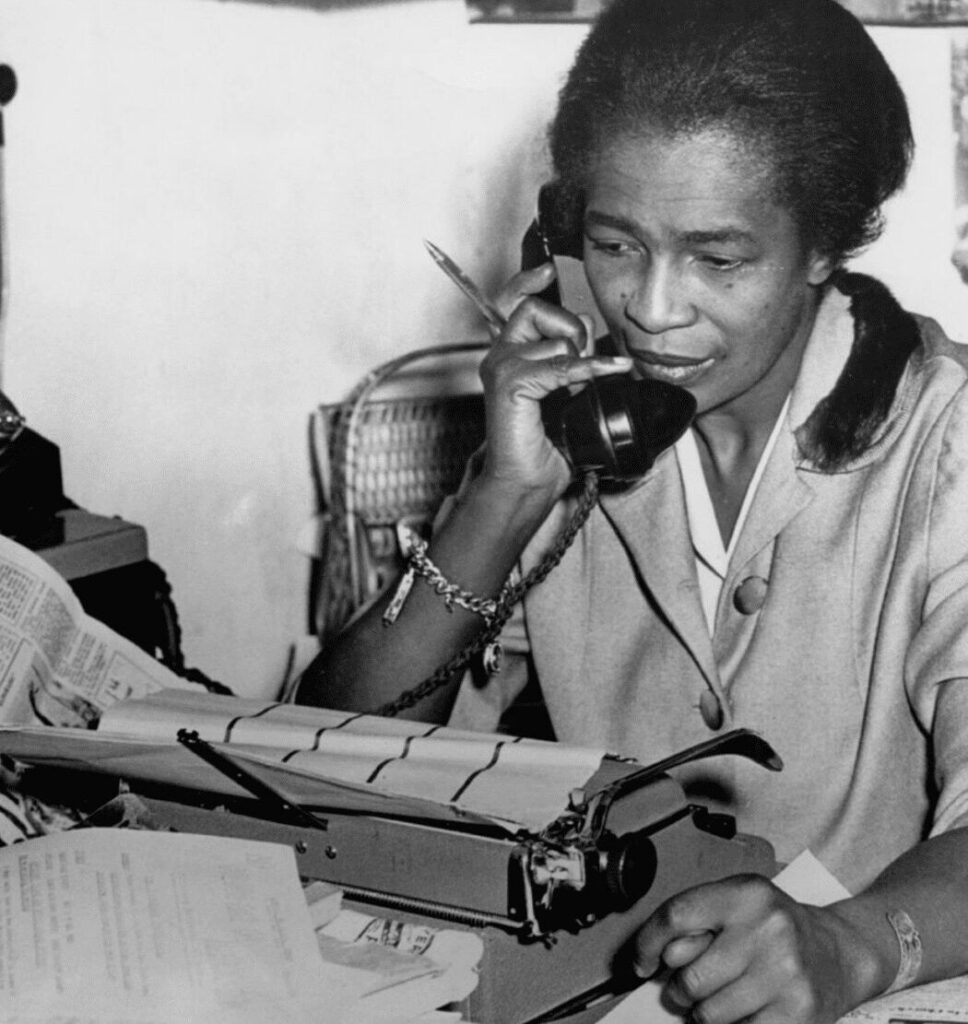

In addition to developing as an effective speaker against injustices, drawing large crowds at meetings throughout the country, Claudia became “negro affairs” editor of the party’s newspaper, the Daily Worker. it was not a favourable time to be a communist in the USA. The Korean war had heightened anti-communist hysteria, leading to the “McCarthy” witch-hunts in the early 1950s.

Claudia was imprisoned four times during these years. As she had not been granted American citizenship, she was deported to the UK in 1955. Her homeland, Trinidad, was then a colony. She settled in West London, around Notting Hill, then a rundown area,and home to the serial murderer, John Reginald Christie.

The “battleground” had been chosen by her opponents. Several racist organisations had moved into Notting Hill. Although much contemporary attention is given to the later participation of the well-known right-wing politician Oswald Mosley, the day-to-day confrontation suffered by the black community was instigated more often by lesser-known troublemakers, particularly the white Defence League led by Colin Jordan. Their provocative marches were intended to goad West Indians into retaliation. They were more successful in persuading a good number of white people to regard the new arrivals as being a threat to their jobs and housing. The escalating tensions erupted in the Notting Hill riots of 1958.

West Indian Gazette

Claudia Jones, living “on the spot” through these incidents and knowing from her American experience where they could lead, did not wait to be overtaken by events. She had the first issues of the West Indian Gazette newspaper out on the streets just before the riots broke out. A community which wants to be heard needs its own voice. And several previous Caribbean/African publications had been the instruments of specific groups or societies, but the West Indian Gazette was the first “black” newspaper to come out (fairly) regularly to meet the more general need. Publication was, in fact, irregular because there was no regular money to meet the printing bills and, it went without saying that the staff, including Claudia herself, were not paid. The few, very few, Caribbean-orientated businesses in the UK were too poor to advertise extensively, and advertising manager Jimmy Fairweather had his work cut out to persuade local businesses that investment would be to their advantage in “getting their message across” to a sector of the public who were already buying their products for lack of any alternative. Nevertheless, the West Indian Gazette had a higher profile than its modest sales would indicate. Situated above a barber’s shop in Brixton – a suburb of inner Southwest London identified then with the Jamaican community – it was in the heart of its intended readership. The newspaper drew attention to issues, personalities, business, politics, and entertainment.

It also provided a grounding for a generation of writers who would go on to shape the Caribbean/African press of this and the next generation. Additionally, a succession of current and future world leaders came to visit Claudia in her humble office. The West Indian Gazette provided a window onto international affairs. This pioneering newspaper – perhaps because it was not dependent on anybody for its financial existence, became a campaigning publication. The Notting Hill riots had opened up debate on a whole series of social issues. Then the 1962 Immigration Act sought to limit the further influx of the population of the (quickly becoming former) colonies. ironically, the desire to “beat the Act” caused those very immigrants to arrive in much higher numbers.

The civil war in the then Belgian Congo was at its height, culminating in an outpouring of grief and indignation at the murder of Patrice Lumumba. South Africa was hardly out of the news with the Sharpeville Massacre, that country’s departure from the Commonwealth, and the trial of Nelson Mandela (and his co-defendants). when the federation of the West indies floundered, Jamaica and Trinidad & Tobago followed Ghana and Nigeria on the path to independence. Since Rosa Parks had challenged bus segregation and federal troops had been called in to enforce integrated education in Little rock, Arkansas, race relations in the US were an ever-present issue of which Claudia had personal knowledge. Fidel Castro’s new leftward leaning, but not yet communist, government in Cuba posed a new challenge to the Americans on their own doorstep.

The West Indian Gazette put these events, and more, in a comprehensive context. Claudia appreciated also the value of presenting culture and entertainment as an antidote to ignorance, and in fostering a sense of common identity.

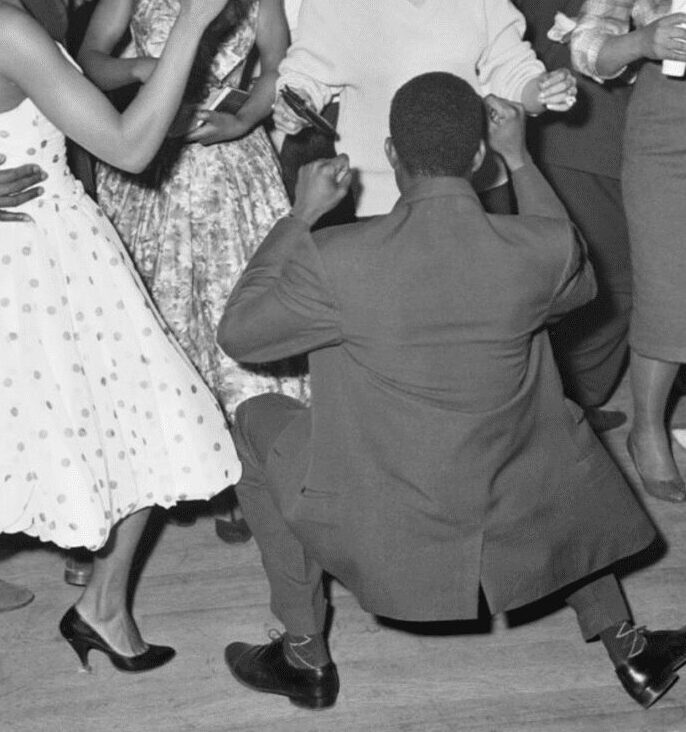

First Carnival

She was a close personal friend of Paul Robeson, the famous American singer, who also suffered in his homeland for his communist sympathies. He was at home in London, well-respected, within a circle of politicians and intellectuals, both Caribbean/African and liberal/socialist Englishmen. Robeson sang for Claudia at fund-raising/awareness enhancing concerts. Even so, after the Notting Hill riots, something special was required, and in the closing months of 1958 the framework of a London/Mardi Gras carnival took shape under the auspices of the West Indian Gazette.

“Claudia appreciated also the value of presenting culture and entertainment as an antidote to ignorance, and in fostering a sense of common identity.”

The initial purpose was “to present West Indian talent to the public which at that time could not see Caribbean people as anything other than hewers of wood and drawers of water”. The first such carnival was held the following January – not at Notting Hill as may be supposed – but indoors at St Pancras Town Hall, in central London. Indeed, I attended my first carnival at the Seymour Hall in London’s West end just a few years later. Claudia called on the support of well-known and accomplished Caribbean entertainers (a good number of whom were Trinidadian) who were beginning to make their mark in the UK. She brought over the Mighty Sparrow, who was, and still is, to calypso what Bob Marley was to reggae.

Notting Hill carnival

The impetus thus started, attracted the support of others with similar ideas, evolving within a short time into the Notting Hill Carnival, which is now one of the world’s major cultural and tourist events.

The election of a Labour government in October 1964 – sweeping away a reactionary conservative administration which was associated in many cases with the worst of colonial attitudes – offered the prospect of the “brave new world” for all, to which Claudia aspired.

Claudia perhaps felt that at long last society could be “getting somewhere”, but life had taught her to be cynical and, in any case, she did not live long enough to prolong the delusion. Following her death, just four more hesitant editions of the West Indian Gazette were published before the newspaper closed down. it seemed that the dream had died with her.

At her funeral, a message from Paul Robeson was read out: “It was a great privilege to have known Claudia Jones. She was a vigorous and courageous leader…and was very active in the work for the unity of white and coloured peoples and for dignity and equality, especially for the negro people and for women.”

Her name has not faded from public memory. In recent years, the Caribbean/African community has reclaimed its heroes and heroines – Claudia Jones among them. In 2007, she received the national accolade of being depicted on a postage stamp and of having a “Blue Plaque” set up in her honour.

The Notting Hill Carnival is a lasting memorial to her aspirations and achievements.