GUEST COLUMN: The Role of Women in Shaping the Climate Mobility Agenda

By Dr. Nassim Majidi and Alessandra Casazza **

“When these environmental shocks happen, men tend to lose hope and you as a woman, you have to be strong for the family because it depends on you. Men also tend to run away from families when situations become tough, so you have to be strong as a woman,” says Mahi*, from Makueni county, Kenya.

Mahi’s story is not hers alone, but that of the many women who are excessively affected by the consequences of climate change. Gender inequality, in fact, manifests itself also during catastrophic weather events, such as droughts and floods, when women are expected to work more as primary caregivers in most contexts. The Global Gender and Climate Alliance and the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) note that “there is a direct relationship between gender equality, women’s empowerment, and climate change. Women are disproportionately vulnerable to the effects of climate change, which could, in turn, exacerbate existing gender disparities.” This is evident in migration contexts where climate change drives men out of their households, leaving women behind facing additional burdens, risks, and exploitation.

As education and livelihood opportunities tend to favour men, too often, women are not given the chance to train and develop skills, limiting their capacity to access information and participate in the decision-making processes.

“There is a direct relationship between gender equality, women’s empowerment, and climate change. Women are disproportionately vulnerable to the effects of climate change, which could, in turn, exacerbate existing gender disparities.”

UNDP

Research by Samuel Hall in Somalia also shows that, in displacement, even when men and women participate in agricultural, construction and mechanical services, women take on lower-paid positions. Internally Displaced Persons women cannot afford not to work, despite extremely low wages and potentially dangerous jobs. The diversification of livelihood sources does not translate into decision-making either. The traditional gender roles put additional pressure on women, who need to perform duties as caregivers, as well as income earners.

Support women’s awareness & preparation

At UNDP, UN Women, and the Africa Climate Mobility Initiative (ACMI) High-Level Forum in 2022, Winfred Lichuma, Chairperson of the Africa Working Group on Gender & Climate Change and the National Gender and Equality Commission for Kenya, explained that opportunities in terms of the nexus across gender, climate change and mobility are largely overlooked, if we only focus on the negative impacts of climate change on women. She added that the involvement of women in critical decisions is lacking, even though their traditional knowledge, lived experiences, and voices have much to contribute to our fight for climate justice. While women continue to account for nearly 62 percent of the labour force across African countries, they only held 29.8 percent of managerial positions in Sub-Saharan Africa in 2020 (UNDP, AfDB, AU and ECA, 2022).

Women are a leading force of adaptation strategies in areas stricken by climate-induced hazards. As men leave in search of livelihood and employment, women involved in agricultural activities develop new ways to cope with climate shocks.

For instance, displaced women whom Samuel Hall interviewed for a study on Climate Adaptive Solutions in Somalia demonstrate that they have a higher level of awareness about adaptive measures to climate risk and environmental degradation. They prefer longer-term strategies, such as planting trees, over shorter-term measures, such as raising the level of the house or moving to another part of the city.

Moreover, in many cultures, women are considered custodians of social norms and have long harboured and passed on practices that are inherently sustainable and rooted in the local context.

Women are a leading force of adaptation strategies in areas stricken by climate-induced hazards. As men leave in search of livelihood and employment, women involved in agricultural activities develop new ways to cope with climate shocks.

Arosha from Somalia says: “We developed adaptive mechanisms by constructing our own houses and adapted to living in this harsh and demanding environment. Our houses were made of branches of trees we cut from the bush.”

Women’s and indigenous communities’ knowledge must be considered when devising policies that concern them as that can play a significant role in preventing climate-induced migration. Indigenous people taking the lead on local solutions is a strategy to enable this. Decolonizing conservation and adaptive climate solutions would be integral to involving women in the climate mobility agenda.

In 2022, the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and partners recognised ten indigenous peoples and local communities from nine countries who won the 13th Equator Prize Award. Among them were the indigenous women of the Sunkpa Shea Women’s Cooperative, in Ghana. By planting indigenous shea trees, these women contribute to restoring the ecosystem, preventing land degradation and, wildfires, ultimately building community resilience in an area prone to drought, and preventing climate-induced displacement. Women’s association is instrumental to women-led natural resources management and protection of ecosystems. “We all come together to earn a living while protecting the environment”, says one of the organizers of the Sunkupa Shea Women’s Cooperative. However, women farmers often lack timely access to climate information which impairs their capacity to make important decisions, such as when and which crops to plant, depending on changing climate patterns.

Training women communicators is also an essential step towards building resilience as women often play a critical role in community development. The Ground Level Report on community-led resilience in the Horn of Africa, which collected primary data in Somalia, Ethiopia and Kenya (IGAD, UNDP, NORCAP, forthcoming) reveals that supporting women’s leadership and their decision-making roles is key and provides them with the necessary resources and skills to implement effective adaptation strategies.

This also lays the foundation for cross-regional and cross-border practices for communities to learn from each other.

Partnerships, Policies & Programming – The Way Forward

Reflecting on the opportunities that exist in the nexus across gender, climate change and mobility, Samuel Hall and UNDP call for a stronger engagement of development partners in support of women’s collective action on climate change and mobility. This can be done in several ways:

- Invest in multi-stakeholder and women-led coalitions to support women facing the muti-layered challenges of climate change, conflict, and displacement. For example, the UNDP Sahel Resilience Project, funded by Sweden, brought together, in August 2022, women leaders, the African Union Commission, ECOWAS, the Community of Sahel-Saharan States, and other stakeholders to ensure that women and girls’ voices are heard in disaster risk reduction efforts.

- Engage in climate policy and diplomacy to account for the situation of displaced women and girls and recognize the opportunities related to the link between gender, climate change, and mobility. This includes identifying policy implications and a legal framework that centre on a gendered analysis of access to assets, roles and responsibilities, income and spending power, and decision-making in displaced communities.

- Expand stakeholder engagement for women, prioritizing a range of partners from various climate-vulnerable regions in order to advocate for more significant investment, aid, and transfer of technology/expertise to and from those localities. Doing so increases the chances to strengthen adaptive capacities and targeted support for the specific protection needs of women.

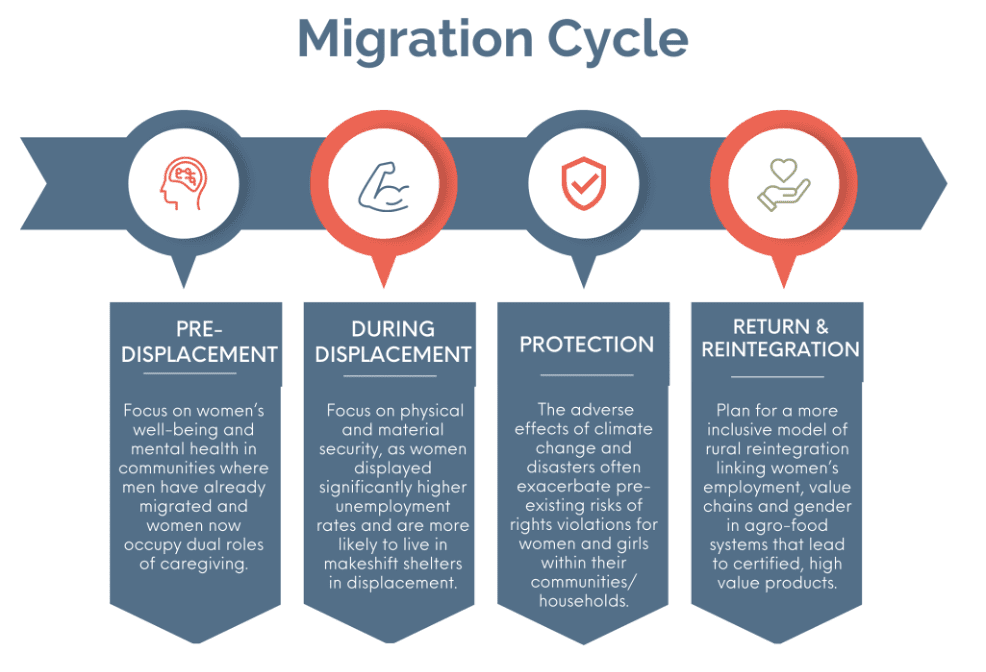

- Expand partnerships across sectors and across time, at different stages of women’s migration cycle. Whilst in displacement, women’s roles change within a context of extreme household vulnerability and with concerning protection risks. Although women are aware of climate shocks, they are less prepared or equipped for what happens in displacement, and upon return. Displaced women are often living in camps where they lack access to healthcare, judicial structures, or protection mechanisms, in contexts where traditional protection structures are weakened. In addition, when the time comes to return to rural areas, women face the additional societal stigma that makes their reintegration more difficult than men’s. The engagement of UNDP in supporting Development Solutions for Internally Displaced Persons is a promising step in this regard.

- Fund women-led environmental programs, that are gender-focused from their design to their monitoring. As Priscilla Achakpa, Global President of the Women Environmental Programme (WEP) in Nigeria, said at the UNDP, UN Women, and ACMI Women’s Forum in 2022, “we want to see policies translate into actions […]; including women, children & the elderly.” These policies and programmes should incorporate monitoring and evaluation of progress using gender-focused indicators. This will ensure that policies/programs are linked with gender commitments, such as CEDAW, the UNFCCC Gender Action plan, and SDGs, as well as the work of ministries on women’s affairs.

- Focus on more inclusive models for rural integration and protection, includingaround gender-based violence in displacement. As Samuel Hall’s research on mental health and climate change in other parts of the world shows, this includes a focus on women’s mental health, as women play the roles of caregivers and caretakers.

- Build research and evidence on the link between climate change, gender, and mobility to identify shared risks and opportunities for solutions, predict potential tipping points, and, most importantly, achieve equity and empowerment. Collaborations with the media and other partners for solid communication and storytelling outputs can promote local knowledge and good practices globally and ensure women’s voices are heard everywhere.

- Change the narrative on female migration with the support of development partners, toconsider voluntary and safe ‘migration’ as a positive adaptive solution for women – one that may open a world of opportunities for both the migrant and the destination. Migration partnerships, particularly with development actors, can and should facilitate forms of mobility that are planned around women’s skills, and profiles, and need to be mutually beneficial. Finally, we must strive for a paradigm and narrative shift to showcase migrants as opportunities and actors of change for the societies that they belong to, temporarily or permanently.

- Dr. Nassim Majidi is the Co-founder and Executive Director of Samuel Hall. zand Alessandra Casazza, Manager of the United Nations Development Programme Resilience Hub for Africa

- Samuel Hall is a social enterprise that conducts research, evaluates programmes, and designs policies in contexts of migration and displacement. Samuel Halls collaborates with a variety of Government partners, civil society, and International Organizations. For this publication Samuel Hall has drawn on work done in partnership with FAO, IOM and UNEP in Somalia and Afghanistan.

- The United Nations Development Programme established in 2019 a Resilience Hub for Africa in Nairobi. It is a “think and do” hub and focuses on priorities such as Accelerating Africa’s Fourth Industrial Revolution, Human Mobility for Development, Climate Resilience, and Governance, Peace, and Security.