Shocking! How George Washington – treated his slaves –some as young as one year old!

George Washington, America’s first and most revered president, had his feet in both slavery and his highly acclaimed fight for freedom and justice for all. A bag of contradictions? Or shame? No wonder the world media has chosen to ignore the story. But welcome to George Washington’s Mount Vernon Estate in Virginia. Your tour guide today is our own editor reGina Jane Jere. She writes;

At the age of 11, George Washington was already a slave-owner, having inherited 11 slaves and 500 acres of land from his father’s will. Eleven years later (at 22), he owned a total of 36 slaves, a dozen of whom were from his uncle, Lawrence Washington, willed to him following the death of both Lawrence’s infant daughter and widow (the would have-been heirs).

By the time he was inaugurated the first president of America in 1789, George Washington was not only the man of his century with a reputation of impeccable honour and integrity, but also the man who held in bondage over 300 slaves, who, after his death (except for one), received their freedom only after his wife, Martha, had died, according to Washington’s will.

This is the story most journalists, particularly in the West, would probably not delve too deep into, as it waters down the adulation that has been piled on the father of American liberty.

But everybody, particularly an African visiting Mount Vernon today, cannot help but feel (even see) the master/slave atmosphere that characterised 18th century life at the Mount Vernon Estate.

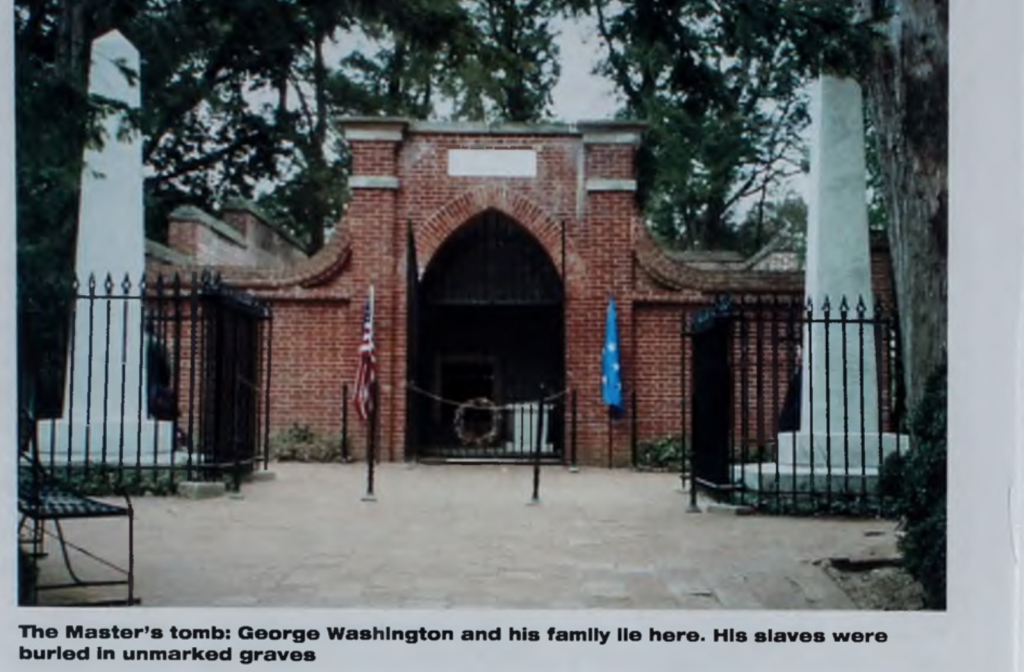

After a fascinating, memorable and impressively narrated tour of where George Washington, lived and how, what and where he ate and entertained his fellow high profile citizens; his private study; and most poignantly the bedroom and bed on which he died (all places still in, or restored to, their original state), it would not be surprising that some visitors may not notice that even in death and hundreds of years later, George Washington is still the Master at Mount Vernon and his slaves are still just that — slaves.

Downhill to the left of the mansion house is the tomb where George Washington, his wife and other family members are gracefully interred, having been moved from another tomb within the estate which fell into a state of disrepair.

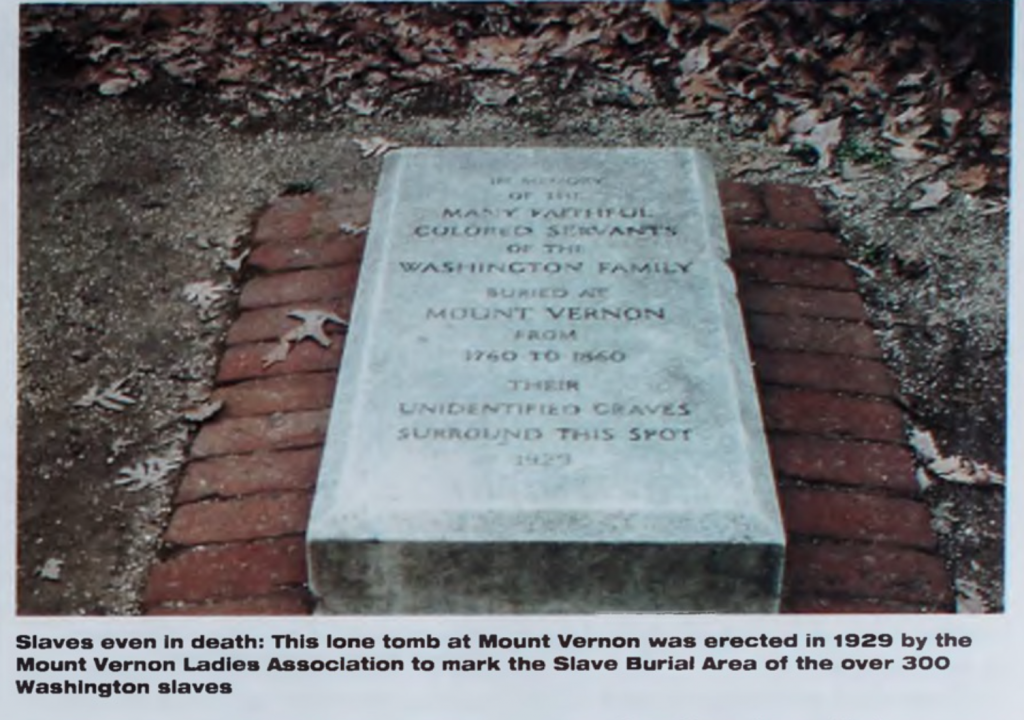

Just a few metres down from where the Master lies, is what is referred to as the Slave Burial Area. This ground is where it is presumed that the over 300 faithful servants that were the lifeline of Mount Vernon may have buried each other.

There is no evidence of any grave, no burial records, not even those of Washington’s trusted servant, Billy Lee, the only slave that the Master’s will said could be freed upon his death.

(Credit: reGina Jane Jere)

Yet the Master personally wrote and kept in descriptive detail lists of all his slaves. On one list, he describes one slave as “a good cutter and mover and can do any other work although defective in shape from his infancy.”

Another one was said to be “a good working woman, notwithstanding her age”. Yet another, called Lucy, is described on another list as “lame or pretends to be so, occasioned by rheumatic pains, but is a good knitter.”

George Washington kept slaves as young as one-year-old.

Our tour

I was in a group of 15 other journalists when I visited Mount Vernon. I wondered during the tour if any of my colleagues felt the same emotions about the place, as I did.

When I saw them move on quickly from the slave burial area, to the next attraction, I knew they did not. I let them go ahead and stayed behind to ponder and imagine what was going on among the souls under the ground on which I was standing.

Right opposite, the Master’s tomb looked imposingly dominant while the ground I stood on felt less significant in comparison.

Once a master always a master – even in death – I pondered.

From where I was standing, I could see a group of 10 to 12-year-old excited school children busily taking pictures of the Master’s resting place. When they moved over to the Slave Burial Area, which some documents have referred to as the most moving spot on Mount Vernon, the children’s cameras stopped clicking.

I heard one of them ask their teacher: “But where are the graves?” The teacher replied; “These people died hundreds of years ago and that is probably why their graves can’t be found today.”

Another child wanted to know why not, because some of the slaves died long after Washington and his family had died. But the school children were quickly chaperoned to the next attraction.

I stayed on, wondering if there was anything the teacher should have said to the last question.

Indeed, generations of American presidents have come and gone since George Washington, but his slaves only came to be honoured with a Memorial Monument in 1983 — over 200 years and 39 presidents later.

This should not be very’ surprising probably, because Washington apparently chose never to speak publicly about his slaves or slavery. When he did, his comments were either feeble or vague.

Yet, the worldwide veneration (including from Africa) of Washington for the good he did for America (and the world) borders on idolatry, obscuring his less talked-about dark side.

The most generally acceptable excuse is that Washington was born and lived in a world that accepted slavery.

Opposition ignored

But opposition to his enslaving of another race while espousing freedom for all, was always there throughout Washington’s private and public life, but he never acted on or responded to it.

In July 1796, one unsung anti-slavery campaigner, Edward Rushton, from Liverpool (England), wrote to condemn and beg in the same breath George Washington, thus:

“It will generally be admitted, Sir, and perhaps with justice, that the great family of mankind were never more benefited by the military’ abilities of any individual, than by those which you displayed during the American contest…

“By the flame which you have kindled, every oppressed nation will be enabled to perceive its fetters… But it is not to the commander in chief of the American forces, nor to the president of the United States, that I have ought to address. My business is with George Washington of Mount Vernon in Virginia, a man who notwithstanding his hatred of oppression and his ardent love of liberty, holds at this moment hundreds of his fellow beings in a state of abject bondage.

“Yes, you who conquered under the banners of freedom, you who are now the first magistrate of a free people are (strange to relate) a slave holder… Shame! Shame!

“That man should be deemed the property of man or that the name of Washington should be found among the list of such proprietors, ages to come will read with astonishment that the man who was foremost to wrench the rights of America from the tyrannical grasp of Britain, was among the last to relinquish his own oppressive hold of poor unoffending Negroes.

“In the name of justice, what can induce you thus to tarnish your own well-earned celebrity and to impair the fair features of American liberty with so foul and indelible a blot?”

The Gift of Silence

Apparently, Washington whom some historians say was thin-skinned to criticism was so angry with Rushton that he fired a letter back to him straightaway.

Like most of his peers, Rushton was incensed with Washington’s lack of political courage to deal with the slavery issue. The reasons why he never took advantage of the colossal public reverence to his statesmanship and presidency to speak out against slavery, is something he took with him to the grave.

“On no occasion did he reveal publicly his own antipathy toward the institution or his privately expressed hopes that it would either wither naturally or be abolished by legislative action,” says Dorothy Twohig who has written extensively on the controversy of Washington’s participation in slavery.

She says in one of her papers that Washington “developed a quality rare among American politicians of any era— he had learned early that it would not be necessary to retract or explain or apologise later for what he had not said in the first place.”

His vice president, later second US president, John Adams, once said of his former boss: “He had the gift of silence.”

In one of his rare, albeit private, remarks on slavery, Washington wrote in 1786:

“I never mean (unless some particular circumstance should compel me to it) to possess another slave by purchase; it being among my first wishes to see some plan adopted by the legislature, by which slavery in this country may be abolished by slow, sure and imperceptible degrees.”

In the same year, he wrote of slavery to his friend, Robert Morris, thus:

“I can only say that there is not a man living who wishes more sincerely than I do, to see a plan adopted for the abolition of it, but there is only one proper and effectual mode by which it can be accomplished, and that is by legislative authority; and this as far as my suffrage will go, shall never be wanting.”

His silence on slavery however bewildering it may seem, was for a reason. Twohig, supported by other reports at the Library of Congress in Washington DC, asserts that Washington’s principal reason for owning slaves and keeping quiet about it, was an economic necessity — without the slaves, there would never have been a vibrant economic life at Mount Vernon.

Poor Creatures

His slave inventories, which he personally prepared and wrote, indicate the number of slaves employed at Mount Vernon at various times over the years. For example:

- In 1759, he owned 24 slaves under the age of 16;

- in 1786 he owned slightly over 100 slaves on his own, with 113 dower (real estate) slaves.

- In 1799, there were 164 Washington slaves and 153 dower slaves.

The dower slaves belonged to his wife, Martha. She had inherited them after the death of her first husband, Daniel Parke Custis.

In Virginia, slavery created a special situation. Slaves were personal property and by retaining dower in personal property, these colonies kept slaves and dower land together.

From 1705 to 1792, Virginia redefined slaves as real property — like the land itself — so the widow/widower could not sell or bequeath slaves at will. At one’s death, the slaves went with the land to the owner’s heirs.

Even during his time as president, Washington always had his slaves close to heart, always wanting to know about their lives and well-being.

Some of his archived correspondence to his managers at Mount Vernon show that as a matter of plantation policy, Washington did not want slaves worked when they were ill and provided medical care, food, clothing and decent accommodation.

For example, he wrote in a letter to one of his farm managers in 1792: “It is foremost in my thoughts, to desire you will be particularly attentive to my Negroes in their sickness; and to order every overseer positively to be so likewise; for 1am sorry to observe that the generality of them view these poor creatures in scarcely any other light than they do a draught-horse or ox; neglecting them as much when they are unable to work, instead of comforting and nursing them when they lie on a sickbed.”

Contradictions

Compassionate as this may sound, his critics believe this apparent benevolence was mainly to his advantage — a healthy slave workforce was good and necessary for the economy of Mount Vernon. Therefore, his economic interests ruled over his moral principles.

Additionally, not only did he need slaves to work his own plantation, he was also aware that much of the golden age of economic and social expansion of his time rested on the slave trade and ownership.

Indeed, different research into the conditions of slavery at Mount Vernon reveal serious inconsistencies between what Washington said and what actually happened.

For example, in 1775 Washington accepted, in settlement for a debt a slave in Maryland who put up a spirited resistance to being separated from his family.

He wrote to his manager of his “reluctance to offer these people at [a] public venue …if these poor wretches are to be held in a state of slavery, I do not see that a change of masters will render it more irksome, provided husband and wife, and parents and children are not separated from each other, which is not my intention to do.”

On yet another occasion, writing to another of his managers, Washington expressed his wish to exchange slaves for land.

“I had rather give Negroes, if Negroes would do, for to be plain, I wish to get quit of Negroes.”

In 1772, Washington was a member of the House of Burgesses which drafted a petition to the King of England labelling the importation of slaves into its colonies from the coast of Africa, “a trade of great inhumanity” that threatened the “very existence of your Majesty’s American dominions.”

Two years later, Washington contributed to the Fairfax Resolves, one of which recommended that no slaves should be imported into the British colonies. The resolutions declared “our most earnest wishes to see an entire stop forever put to such a wicked, cruel and unnatural trade.”

But despite all this, Washington’s real conduct was devoid of signs that showed he had moral and ethical concerns on slavery or whether this really troubled him. Instead, he increased his slave labour force on his plantation as the years went by.

Not wanted: Negroes in the army

Ironically, Washington was at the same time strongly opposing the recruitment of blacks into the army during the American Revolution. Historic documents indicate that he objected to using black soldiers for fear that arms-bearing slaves could agitate for a revolt in their circles.

At the end of the war, writes Twohig, Washington made somewhat half-hearted efforts to send back slaves who had run away from their masters to enlist, and to order courts of enquiry for those who were now claimed by their masters.

In 1783, he objected to British plans to take with them slaves who had served with the British army, arguing that the provisional articles of peace prohibited such removal.

On the other hand, he approached one of the agents overseeing the departure of the British, contending that some of his own slaves and those of his wartime manager, Lund Washington, might be in New York, and asked the agent to help with their return, mostly likely to Mount Vernon.

During the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia over which he presided, Washington was fully aware of the implication slavery presented at the deliberations. The delegates were more concerned with seeing the success of a new government that they were not willing to sink their ship by allowing slavery to disturb the agenda for the new republic.

Hence in their debates, writes Twohig, “the delegates trod so delicately that they employed euphemisms to avoid even the use of the word [slave]; slaves were disguised as “persons,” or “persons held to service or labour”; the slave trade became “migrations”.

Washington, like many others of his post-Revolutionary generation, still blamed Britain for hanging slavery around colonial necks, and hence anti-slavery sentiment came in a poor second when it conflicted with the powerful economic interests of pro-slavery forces.

“To Washington as to many Americans,” Twohig explains, “even some whose opinions on slavery were far more radical than his own, the institution had become a subject so divisive that public comments were best left unsaid.

“For Washington, as for most of the other founders, when the fate of the new republic was balanced against his own essentially conservative opposition to slavery, there was really little contest. And there was a widely held, if convenient, feeling among many opponents o f slavery that, if left alone, the institution would wither by itself,” Twohig adds.

Hence publicly no comments came from Washington on slavery.

But even during his presidency, Washington’s attitude to slavery was not impressive. According to documents in the Library of Congress, in April 1791, fearing the impact of a Pennsylvania law freeing slaves after six months residence in that state, Washington instructed his secretary, Tobias Lear, to ascertain what effect the law would have on the status of the slaves who served the presidential household in Philadelphia.

In case Lear believed that any of the slaves were likely to seek their freedom under the Pennsylvania law, Washington said they should be moved to Mount Vernon.

“If upon taking good advise it is found expedient to send them back to Virginia, I wish to have it accomplished under pretext that may deceive both them and the public,” the freedom and liberty loving Washington ordered Lear.

When one of his slaves ran away in 1795, Washington told his overseer to take measures to apprehend the slave. “But 1 would not have my name appear in any advertisement, or other measure, leading to it.”

Freedom and justice indeed!

French lessons

If Washington still had any doubts concerning reaction in the United States to the spectre raised by the question of emancipation, public reaction towards the slave revolt in the French colony of Saint Domingue (now Haiti) in 1791, may have helped confirm his determination to avoid pursuing the issue at all costs.

Twohig writes: “The horrors of the revolt of the slaves on Saint Domingue against their French masters were immediately apparent, although less understood in the United States were the appalling conditions that had inspired the revolt. “Daily reports appeared in American newspapers on the insurrection. The revolution struck Americans on two fronts. It played to their views of the sanctity of property, which to most Americans was part of the basic natural rights for which they had fought Britain for nine long years, and it fed the fear, bordering on paranoia, in the deep south of slave insurrections.”

Washington responded by writing to Jean Baptiste de Ternant, the French minister, promising to provide money and arms requested by the French government to quell the revolt.

“I am happy in the opportunity of testifying how well disposed the United States are to render every aid in their power to our good friends and allies, the French, to quell ‘the alarming insurrection of the Negroes in Hispanola’ and of the ready disposition to effect it, of the executive authority thereof,” Washington wrote to Ternant.

Therefore, to this day, Washington’s occasional comments on slavery expressing his desire to see it disappear are mired in confusion and contradictions.

It is likely that he disapproved of slavery on moral grounds, yet he considered slavery vital to economic development. In fact, there is no indication in his correspondence that he ever advocated any immediate abolition policy.

Today his ownership of slaves and his failure to speak out publicly against slavery is still, to many, a hard fact to take in.

The generally accepted argument of forgive and forget, because Washington was born and lived in an era when slavery was “acceptable” holds no water. Acceptable to whom and for what?

George Washington died knowing to his last day that slavery was wrong, but chose to do nothing about it. The consequences of his action are still being felt today and no one is taking responsibility for what America’s most adored symbol of freedom, could have avoided centuries ago.

He had the power to do so.

George Washington’s Will regarding his slaves

“To my dearly beloved wife Martha Washington, I give and bequeath the use, profit and benefit of my whole estate, real and personal, for the term of her natural life… Item: Upon the decease of my wife, it is my will and desire that all the slaves which I hold in my own right, shall receive their freedom.

To emancipate them during her life, would, tho’ earnestly wished by me, be attended with such insuperable difficulties on account of their intermixture by marriages with the dower Negroes, as to excite the most painful sensations, if not disagreeable consequences from the latter, while both descriptions are in the occupancy of the same proprietor; it not being in my power, under the tenure by which the Dower Negroes are held, to manumit them.

And whereas among those who will receive freedom according to this devise, there may be some, who from old age or bodily infirmities, and others who on account of their infancy, that will be unable to support themselves; it is my will and desire that all who come under the first and second description shall be comfortably clothed and fed by my heirs while they live; and that such of the latter description as have no parents living, or if living are unable, or unwilling to provide for them, shall be bound by the court until they shall arrive at the age of 25 years; and in cases where no record can be produced,

whereby their ages can be ascertained, the judgement of the court, upon its own view of the subject, shall be adequate and final.

The Negros thus bound, are (by their masters or mistresses) to be taught to read and write; and to be brought up to some useful occupation, agreeably to the laws of the Commonwealth of Virginia, providing for the support of orphan and other poor children.

And I do hereby expressly forbid the sale, or transportation out of the said Commonwealth, of any slave I may die possessed of, under any pretence whatsoever.

And I do moreover most pointedly, and most solemnly enjoin it upon my executors hereafter named, or the survivors of them, to see that this clause respecting slaves, and every part thereof be religiously fulfilled at the epoch at which it is directed to take place; without evasion, neglect or delay, after the crops which may then be on the ground are harvested, particularly as it respects the aged and infirm; seeing that a regular and permanent fund be established for their support so long as there are subjects requiring it; not trusting to the uncertain provision to be made by individuals.

And to my mulatto man, William (calling himself William Lee,) I give immediate freedom; or if he should prefer it (on account of the accidents which have befallen him, and which have rendered him incapable of walking or of any active employment) to remain in the situation he now is, it shall be optional in him to do so.

In either case however, I allow him an annuity of $30 during his natural life, which shall be independent of the victuals and clothes he has been accustomed to receive if he chooses the last alternative; but in full, with his freedom, if he prefers the first; and this 1give him as a testimony of my sense of his attachment to me, and for his faithful services during the Revolutionary War. “

This article was originally Published in the May Edition of New African Magazine 2001 of which reGina Jane Jere was its Deputy Editor at the time.