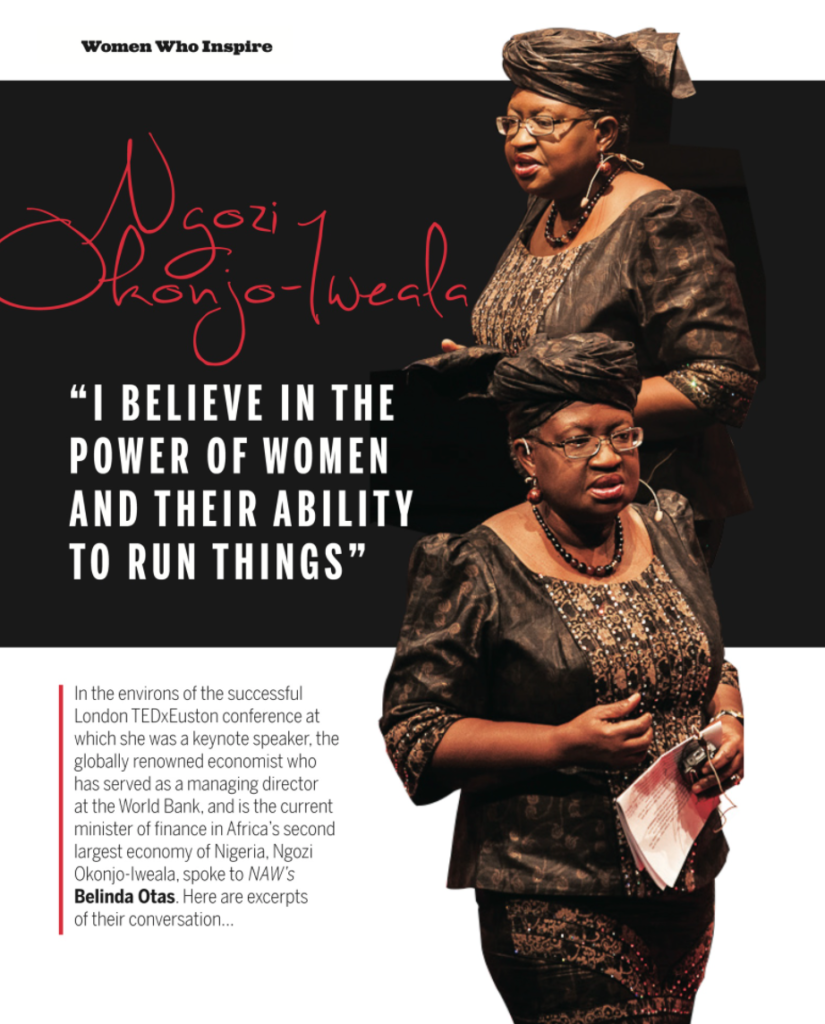

INTERVIEW. Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala: “I believe in the power of women and their ability to run things.”

Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala, is frontrunner in the race to become the head of the World Trade Organisation (WTO). Come 9 November, the former Finance Minister in Nigeria, could become the first female, and African to head the organisation. We revisit our interview with her, to reminisce why she is not only one of Africa’s most influential women, but ticks all the boxes for this instrumental position.

On 28 October, following a procedural nomination meeting, the WTO announced that based on its outcome, “the candidate best poised to attain consensus and become the 7th Director-General was Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala of Nigeria.”

She reacted to the news in a tweet to her 1.2 million followers: “Happy for the success and continued progress of our @wto DG bid.Very humbled to be declared the candidate with the largest, broadest support among members and most likely to attract consensus. We move on to the next step on Nov 9, despite hiccups. We’re keeping the positivity going!”

The hiccups she could be referring to could be the vehement opposition to her candidacy, by the United States who favour the appointment of the other remaining candidate – South Korea’s Minister of Trade Yoo Myung-hee. They are vying to succeed Brazil’s Roberto Azevêdo, who stepped down in August.

Dr Okonjo-Iweala’s CV is perhaps one of the finest. She is a global finance expert, an economist and international development professional with over 30 years of experience working in Asia, Africa, Europe, Latin America and No1th America. Currently, Dr Okonjo-lweala is Chair of the Board of Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance.

Since its creation in 2000, Gavi has immunized 760 million children globally and saved thirteen million lives. She sits on the Boards of Standard Chartered PLC and Twitter Inc. She was recently appointed as African Union (AU) Special Envoy to mobilise International financial support for the fight against COVID-19 and WHO Special Envoy for Access to COVID-19 Tools Accelerator. She is a skilled negotiator and has brokered numerous agreements, which have produced win-win outcomes in negotiations.

She is regarded as an effective consensus builder and an honest broker enjoying the trust and confidence of governments and other stakeholders.

Previously, Dr. Okonjo-lweala twice served as Nigeria’s Finance Minister (2003-2006 and 2011-20 I 5) and briefly acted as Foreign Minister in 2006, the first woman to hold both positions.

She distinguished herself by carrying out major reforms, which improved the effectiveness of these, two Ministries and the functioning of the government machine1y. She had a 25-year career at the World Bank as a development economist, rising to the post of Managing Director, Operations.

As a development economist and Finance Minister, Dr Okonjo-lweala steered her country through various reforms ranging from macroeconomic to trade, financial and real sector issues.

Excerpts from our interview:

NAW: You are responsible for one of Africa’s biggest economies. Do you feel a sense of heightened responsibility especially as a woman and being the first woman to hold that position in the history of Nigeria?

Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala: (Laughs)I don’t go around everyday thinking I’m a woman, but I love being a woman. It’s natural and I think it brings certain advantages and clarity of thinking in purposeful delivery and focus on results and wanting to do the right thing. My job is to be the best professional that I can be and the best finance minister that I can be and work as hard as I can, so that the next time, they will just take the best person for the job and that best person could be a woman.

You open the door by doing your work. When a choice is being made, there’s no inhibition of saying she is a woman, she might not be able to deliver. It’s not a numbers game. It’s really a responsibility game.

Of course, it’s a sense of responsibility to serve my country, which is what brought me into the job in the first place. Being a finance minister is such a thankless and difficult job and you can ask any finance minister anywhere in the world, you have to make decisions nobody likes, but you are not there to be liked. You are there to get work done and get respect and you have to have a sense of commitment because it’s very challenging.

Everyday, there are people criticising you right, left and centre. So you have to be grounded in knowing that there are a set of principles that guide the work. You have to recognise that you also have to work with a team. You don’t achieve or get the job done on your own and you have to motivate the team to help you deliver. So it’s a very difficult work that comes with a sense of responsibility.

Having read your book, Reforming The Unreformable:Lessons from Nigeria, one can tell that you place great value on teamwork. From a woman’s perspective, why should women change the way we look at collaboration between women in order to advance economically, socially and politically?

I think a lot of it is a trust issue. You need to build trust with other women and women need to believe in themselves. There are many women who may be working but they don’t believe in themselves or other women and in their mind, they still think that men are the decision-makers and it’s men that they look to. They do not see other women as leaders.

They see them as competition. For me, the platform is big and the more women, particularly young women, you can get up there and motivate, the more powerful you will be. So when I see other women, I always look on them as a potential source of collaboration. But then you have to be careful because you may be looking at them like that and they may be seeing you in a totally different light that you don’t know about.

That has happened to me quite often – working with other women, you have groomed them and worked with them, mentored them, then when they get into a position they promptly turn around and stab you in the back big-time. I have experienced that too and it’s not a pleasant thing, but that has not taken away my strong belief in women. African women are really strong; they do so much and deliver so much. I believe in the power of women and their ability to run things.

In terms of mentoring and helping other women come through the door, what’s the legacy that you would like to leave?

Well, the legacy I can leave is by showing that you can do it. I trust that younger women can look at what I did and they can find out that you can have your career, marry and have a family. It’s not easy by the way and I’m not saying that everybody can automatically do it. You have to find your own balance. Hopefully I can serve as an example.

Secondly, I personally mentor young women and it’s not only young African women. I mentor Chinese, Asian, African and European women. I also mentor men when they come for advice and guidance in addition to my own children. That means you devote time and when they have a problem, you have to listen to them. But mentoring is intensive.

Hence, when someone comes and says, “can you be my mentor?”, I hesitate because I can only do so much. Working with me is also mentoring because you learn just as I learn from other people. But I would say to women, find something that you are passionate about, find something that drives you, something that you have a commitment to, something you want to change.

You have made youth economic empowerment an area of focus. Where does your passion for the next generation come from and what is the potential that you recognise that encourages you to keep pushing for it?

I just like engaging with young people. I don’t know why. They give me energy. When I’m with young people, I feel energised, really happy, and good and I feel they have so much to offer. When I listen to them, particularly when they are trying to do something that gives back and or they are coming up with new ideas, I feel I can learn from young people and I like learning. You are never too old to learn.

If you ever stop learning in life, then you know something is really wrong. Even when I was at the World Bank, I always surrounded myself with younger economists and as a minister, you can see my office, I have a lot of young people and they work so hard. But most of all, you can encourage them to lift their sights and grasp what is waiting for them.

What are the challenges of being a reformer given the criticism that comes with the territory?

Very few people want to be reformers because it’s not a fun job, but you have to ask yourself why you want to do it and what needs to be done. Do you have the necessary landscape and political backing to be able to do it? I think in our countries, and if we really want the African continent to sustain the growth and development beyond what we have seen, we have got to keep reforming a whole range of sectors; we really have a long way to go.

The issue is that in every sector, you are reforming because things are not working well or there is a missing link, but there are also people who have been in that sector benefiting and we call them vested interests and it’s to their advantage that you don’t do anything or you don’t succeed, so they can continue benefiting. So that’s the drawback of vested interests, even if you are trying to clean up. Whatever you are doing, they are there.

—–

This interview was first published in Issue 24 of our Print Edition, when NgoziOkonjo-Iweala was Nigeria’s Finance Minister. We had caught up with her at London’s TEDxEuston 2014 where she was keynote speaker.